Architect, artist and editor of Raya Editorial, with an internationally recognised career, the photographer and photography promoter Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo is part of the Jury of Honour of the PHotoFUNIBER’25 International Photography Competition.

Winner of prizes awarded by prestigious institutions in the field of photography, Escobar-Jaramillo is an art activist, promoting, through collectives, publishers, workshops, courses and curatorships, knowledge and various talents, especially in the Latin American context.

We interviewed him to find out about some of his reflections and work:

In your opinion, what is a ‘good photograph’?

To put it dryly, a ‘good photograph’ is one that looks good to us. I think the lines that divide what is good and what is bad in a photo lie very much with the photographer and the viewer. The classic sense of composition and light depends a lot on what we want to say and the format in which we are going to show it.

A photobook, for example, is very hospitable to the ‘bad’ or ‘repeated’ photos it contains, because a bad photo can be useful for an atmosphere, and a repeated photo is necessary to change the rhythm…

At the same time, the needs of an exhibition or a web gallery may require other conditions.

To repeat myself, photography depends a lot on the intention we want to convey or the story we want to tell.

Tell us about some recent work you have done or are doing and the challenges you encountered in developing this project.

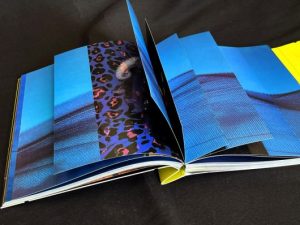

My latest project and photobook ‘El pez muere por la boca’ (Raya Editorial and Matiz Editorial), is a reflection on the resilience and resistance of coastal villages in Colombia in contexts of drug trafficking and fishing.

It studies a phenomenon known as ‘white fishing’: when drug traffickers are intercepted by the naval forces, they throw their cargo into the sea on pain of being caught. These packages of drugs are sometimes picked up by fishermen – who have traditionally made their living from fishing for red snapper, tuna and lobster. The drug loads are sold back to the narcos, and the money brings economic benefits to the fishermen and their families. However, this illegal act puts them in danger of extreme violence and tensions with the community, which takes a dim view of these practices.

Precisely, the project emphasises these non-participating communities and their resilient acts, which can be something as simple – and powerful – as daily gestures, expressed in dance, music, hairstyles, celebrations, tourism, architecture, gastronomy, etc.

I worked in Bahía Solano, Pacific Sea and in Rincón del Mar, in the Atlantic (or Caribbean Sea). In the latter, I have travelled since I was 12 years old to be close to the sea. There I met Deivis and Federico, who have been my local friends since childhood, and it is with them and their families that I have built this project, which has a fundamental characteristic: it is a collaborative project, where the community participates in the creation of the images.

The fish has been exhibited and recognised in at least 25 places around the world. From Bolivia to Japan; from Peñarol to the United Arab Emirates; from Fortaleza to Angkor Wat. Now in April I will exhibit it in Cairo, and in May, in Rotterdam. And it seems important to me to show the project at an international level because in Colombia we have a tragic fate due to violence and drug trafficking; the way we have been pigeonholed from outside, full of common and repeated places, does not allow us to see other values of the communities that resist in silence and with their heads held high.

You are very active in promoting photography at festivals, publishing houses and events. How do you see the photographic sector?

Latam faces simultaneous pressures coming from the north and pushing from the south. Totalitarian and populist governments don’t want us to have access to culture, let alone to be able to express ourselves freely.

The most direct and sincere way to resist these onslaughts is through art. Festivals, publishing houses and photographic events are all platforms to let out the cry and spread the message that each one of us carries within.

That said, it is not easy to finance spaces, but the network that extends between our countries allows for this much needed interconnectivity.

The best advice I can give to those involved in photography is to keep travelling and participating in events. Don’t underestimate the so-called ‘small’ events, because sparks can be born there that can ignite larger flames.

This year, the PHotoFUNIBER International Photography Competition is looking forward to receiving photos on the theme of ‘education’. As a jury, what narratives on this theme would you like to see that are interesting and current?

Education in many places in Latin America is established as a position of Power: that of being able to tell stories from a particular and arbitrary point of view. Education must be rigorous and objective in relation to the facts, but it must also be free and diverse in relation to the different expressions of citizenship.

For the call, I would be interested in seeing unconventional forms of education, both in teaching and learning; the challenges facing education in Latin America; the courageous acts that our social, political, economic and geographical conditions demand; examples that put in tension and critique the current state of things; the adaptation and discernment of new technologies and AI.

Among so many images in which we live, do you think that photography can still move people and provoke reflections on our environment?

Any artistic expression has the potential to move and provoke reflections, because art is constantly renewing itself as it is linked to the senses, emotions, relationships, memory and imagination. Each new step reconfigures these notions and constitutes them as new.

And art is back and forth, requiring a sender (creator) and a receiver (audience); any alteration to these notions, in one sense or the other, regenerates the experience in a constant way. Thus, art, like photography, is dynamic.

Find out more about her work at: @escobart @rayaeditorial http://www.rayaeditorial.co/

UNEATLANTICO Special Award

The PHotoFUNIBER International Photography Competition, organised by FUNIBER, includes the UNEATLANTICO Special Prize, aimed at recognising the talent of students and alumni of the European University of the Atlantic. This prize is awarded to the two best photographs submitted by students or alumni of any UNEATLANTICO degree or bachelor’s degree, and each winner receives a prize of 200 euros.

In previous editions, the winners of the UNEATLANTICO Special Prize have been.

- PHotoFUNIBER’24:

- Urban Oasis, by Barzilai Espinosa Torales.

- Cleaning the water, by Teresa Bear Sierra.

- PHotoFUNIBER’23:

- Much more than fishing, by David Sánchez Andrés.

- Santander through the glass, by Pablo Segura Herreras.

Finally, it should be noted that the winning works are exhibited in the UNEATLANTICO exhibition hall, together with the rest of the winning photographs from the competition.